Four very old plants: Gosslingia, Sawdonia,

Drepanophycus and Zosterophyllum

Plants from the Early Devonian (410 - 380 million years ago) didn't

grow very high. They didn't get much taller than 50 cm. Yet they were much

more complicated than Silurian plants, like Cooksonia. The latter

plant was mostly much shorter than 10 cm, didn't have leaves, was bifurcating

and bore sporangia at the top of the little stems. The plants presented here

showed already much more differentiation.

Devonian plants are usually only fragmentarily preserved. This is on the

one hand a consequence of the age and on the other hand because

the circumstances for fossilisation were unfavourable. And even if somewhere

many plant remains are found, they are generally heavily damaged. This is

certainly the case for the first plant below. |

Gosslingia breconensis

This plant is found in several places in the world, but it was described

by Heard in 1927as a result of finds in a quarry in the Brecon Beacons (Wales):

this explains the species name. In 1970 Prof. Dianne Edwards of the Cardiff

University described it again very extensively.

My wife

and I have visited this quarry several times and we found out that there

are vast amounts of plant remains, but hardly any pieces with structure,

like branchings or sporangia. Most of the remains are thin stems with a maximum

length of 20 cm. Often they are embedded more or less parallel which

is an indication for flowing water during the sedimentation. My wife

and I have visited this quarry several times and we found out that there

are vast amounts of plant remains, but hardly any pieces with structure,

like branchings or sporangia. Most of the remains are thin stems with a maximum

length of 20 cm. Often they are embedded more or less parallel which

is an indication for flowing water during the sedimentation.

Still we found some branched stems and also a couple of coiled tips.

But the most wanted sporangia, which are of vital importance for identifying

Devonian plants, remained hidden.

When I went through the crates with fossils from the quarry again, some

big slabs appeared which I had taken along because they looked promising.

From these slabs two very fine specimens appeared, showing bifurcations,

sporangia and coiled tips.

Click on the

photo on the left to see a reconstruction and a photo of one of these plants.

Click on the right hand one to see the other specimen. The quality is not

comparable to the preservation of e.g. plants from the Coal Measures but

by Lower Devonian standards the fossil is very complete. The sporangia are

clearly visible along the stems and also some curled tips (a characteristic

of many primitive plants) are present. Click on the

photo on the left to see a reconstruction and a photo of one of these plants.

Click on the right hand one to see the other specimen. The quality is not

comparable to the preservation of e.g. plants from the Coal Measures but

by Lower Devonian standards the fossil is very complete. The sporangia are

clearly visible along the stems and also some curled tips (a characteristic

of many primitive plants) are present.

The stems branched bifurcating with alternately a left hand branch being

thicker and a right hand branch being thicker. In this way a kind of main

stem came into existence. This kind of branching is called 'pseudomonopodial'.

It can be regarded as a transitional stage between bifurcating (like

Cooksonia) and a main axis with side branches.

As far as I know only less complete fossils of this plant have been

found at other sites (e.g. in Belgium).The age of the plants is Siegenian

(about 400 million years). |

Sawdonia ornata

I saw this plant for the first time in an abandoned quarry near Glasgow.

Nowadays it is a protected area, but at the time it (luckily) wasn't yet.

The quarry was very wet and overgrown, but there was still a vertical face

where the rock was accessible. This face was crumbling off under the plentiful

rain, causing pieces of sandstone regularly to fall down. In these soaked

fragments were black stems with spines. These turned out to be stems of the

species Sawdonia ornata.

This is also a fossil with a history. Dawson named the plant in 1871

Psilophyton princeps var. ornata because he regarded it as

a spiny form of Psilophyton princeps. The latter plant bears sporangia

in pairs at the end of the stems. Later on it was found out that the sporangia

of the spiny plant were not terminal, but that they were placed

laterally at the side of a stem (as a loose spike). Then in 1971 Hueber placed

the plant into a new genus and he named the plant: Sawdonia

ornata.

Click on the photo to see a reconstruction and a photo.

The function of the spines is not clear. They could have had a repelling

task against arthropods, which were already present at the time. It is also

possible that the plants could hold dew with the spines.

The tips of the stems,

the growing points, were coiled. In between the fossils of the spiny axes

such spirals are sometimes found. They have not yet been found attached to

a stem, but the cell structure of the cuticle, the waxlike layer which

protects the plant, proves that they certainly belong to this species. The tips of the stems,

the growing points, were coiled. In between the fossils of the spiny axes

such spirals are sometimes found. They have not yet been found attached to

a stem, but the cell structure of the cuticle, the waxlike layer which

protects the plant, proves that they certainly belong to this species.

Sporangia of this plant are very rare: Rayner (1983) wrote that in this

quarry only four specimens of Sawdonia ornata with sporangia had been

found. After reading this I have worked through my crates with fossils again

and the first specimen I took in my hands turned out to be such a typical

spike: a stem with black spots alternating left and right of the stem.

Click

on the photo on the left. The preservation is not very good, but the same

can be said of the plants of Rayner. In spite of the fast find I had no more

specimens in my crates. Click

on the photo on the left. The preservation is not very good, but the same

can be said of the plants of Rayner. In spite of the fast find I had no more

specimens in my crates.

The sporangia are round or oval and are placed, like the side axes,

alternating on the main axis. The bad preservation is likely to be due to

the coarse basic material of the sandstone of the quarry.

Sawdonia ornata is also found in many other places, but not often

as complete as in this one. The age is Emsian (395 million years).

|

Drepanophycus spinaeformis

This

is also a spiny plant, like Sawdonia, but yet there is a difference.

In Drepanophycus the spines are called leaves. This is because a vascular

bundle is running through. Also the 'spines' do have a different shape compared

with those of Sawdonia: they are broad at the base and are tapering

to the apex and often they are somewhat bent (more or les sickle-shaped).

They can reach a length of 2 cm, but the average size is 1 cm. Click on the

photo on the right to see a larger photo and a reconstruction of the

plant. This

is also a spiny plant, like Sawdonia, but yet there is a difference.

In Drepanophycus the spines are called leaves. This is because a vascular

bundle is running through. Also the 'spines' do have a different shape compared

with those of Sawdonia: they are broad at the base and are tapering

to the apex and often they are somewhat bent (more or les sickle-shaped).

They can reach a length of 2 cm, but the average size is 1 cm. Click on the

photo on the right to see a larger photo and a reconstruction of the

plant.

Unfortunately

the leaflets are missing in most cases. This has to do with the

circumstances during the process of fossilization. At some sites,

like in New Brunswick in Canada, near Dave in Belgium and in the quarry near

Glasgow mentioned before, better and more complete specimens have been found. Unfortunately

the leaflets are missing in most cases. This has to do with the

circumstances during the process of fossilization. At some sites,

like in New Brunswick in Canada, near Dave in Belgium and in the quarry near

Glasgow mentioned before, better and more complete specimens have been found.

Fossils with sporangia, however, are extremely scarce.

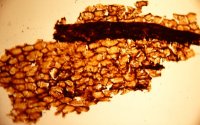

We have found Drepanophycus spinaeformis at several places in

Belgium, Great Britain and Germany, but in most cases it was only the main

axis without leaflets. This axis can be recognized by its diameter (up to

4 cm) and by its irregular, bubbled surface (click on the photo on the left).

In fact there are no other plants from the Lower Devonian showing these

characteristics. When the axes are thinner, confusion with Sawdonia

is very likely. In that case attached spines, if any, must give clarification.

The

sporangia are attached with a small stalk directly to the axis. Finding,

however, a specimen with sporangia is like winning a jackpot in a lottery.

Still we have won a smaller prize in the Glasgow quarry, namely a piece of

the cuticle of the plant. After a chemical treatment I made a microscopic

slide, on which the cell structure is clearly visible. Click on the

photo. The

sporangia are attached with a small stalk directly to the axis. Finding,

however, a specimen with sporangia is like winning a jackpot in a lottery.

Still we have won a smaller prize in the Glasgow quarry, namely a piece of

the cuticle of the plant. After a chemical treatment I made a microscopic

slide, on which the cell structure is clearly visible. Click on the

photo.

Probably the plant was growing on planes along the river which became

inundated periodically. The parallel embedding of the stems at some places

indicates that some vegetations were fossilized in situ. In these cases the

quality of the fossils is often very good.

There has been a lot of discussion about the question how this plant

must be classified, but nowadays it is assumed to be an early lycopod. |

Zosterophyllum myretonianum

The

genus Zosterophyllum serves as a model for a large group of plants,

the Zosterophylls, into which also the first two plants of this chapter,

Gosslingia and Sawdonia, are included. This group was in existence

from the Late Silurian until the Late Devonian and is narrowly related to

the lycopods, which includes Drepanophycus. An important characteristic

of the Zosterophylls is the fact that the sporangia are laterally borne along

the stem (and not at the end like in Cooksonia). In many cases they

form a kind of a spike. Furthermore the growing tips of the stems are coiled

(like young ferns). Click on the photo to see a larger photo and a reconstruction

of the plant. The

genus Zosterophyllum serves as a model for a large group of plants,

the Zosterophylls, into which also the first two plants of this chapter,

Gosslingia and Sawdonia, are included. This group was in existence

from the Late Silurian until the Late Devonian and is narrowly related to

the lycopods, which includes Drepanophycus. An important characteristic

of the Zosterophylls is the fact that the sporangia are laterally borne along

the stem (and not at the end like in Cooksonia). In many cases they

form a kind of a spike. Furthermore the growing tips of the stems are coiled

(like young ferns). Click on the photo to see a larger photo and a reconstruction

of the plant.

The name Zosterophyllum comes from Penhallow, who gave it in

1892 to plant remains resembling sea grass (in Latin:

Zostera). The meaning of the name is therefor: plant with sea

grass-like leaves.

We made our own finds mainly in the old quarries in het region of Forfar

in Scotland. The rock in some of the quarries is full of long, bent plant

stems. Sometimes they lie more of less parallel, but mostly they in a jumble.

There is little structure to see and branching stems are very rare. I know

from the literature that the plant is named Zosterophyllum myretonianum,

but identifying one yourself is hardly thinkable. As so often in Lower Devonian

plants, scientists need the very rare , complete specimens to know more about

a plant. That's why I was very happy to find the spore cone on the photo

above.

Click on

it. Click on

it.

I have found the coiled tips of the stems only as loose spirals.

Striking are the H- and K-shaped branchings. It is assumed that these

are part of a ground network of horizontally growing stems, which are attached

to the soil by hair roots. Such branchings are not present in upright stems,

moreover the vertical stems branch very rarely. Click on the photo on

the right.

Within the genus Zosterophyllum eight species have been described,

differing from each other in details. |

Conclusion

Reconstructions of Lower Devonian plants are generally achieved with

difficulty because the fossils are usually fragmentary. Often many paleobotanists

were involved and their insights have changed in the course of 150

years or in any case they have become more specific. Collecting this kind

of plants is difficult and time-consuming but by the same token it gives

a lot of satisfaction when you manage to get an image of the complete plant.

It provides a glance at a world of plants which is quite different from the

present one.

Literature

Top |

|